Tag Archives: 2015 Emily Kardamis

Emily Kardamis

Emily Kardamis

Emily Kardamis: Epileptic by David B.

Out of all of the readings during the semester, none of them struck me quite like David B.’s Epileptic did. There was something about the art style that drew me in immediately: I was familiar with that stark black and white style from other graphic novels that I loved, like Maus and Persepolis, so it really hooked me where other readings took some sitting with to really get into. However, Epileptic immediately turned my expectations on their head as it weaved this complex narrative memoir about the author, his family, and how his brother’s illness defined him throughout his life.

Artistically, I was particularly struck with how David B. was able to masterfully use figure ground relations throughout the novel in order to emphasize the balance and chaos of his life: the mythical figures he creates and converses with in the forest are often swathed in harsh spot blacks, the bird-like specter of death that haunts him and his mother is almost entirely in black, and his brother’s epilepsy (as well as his own mental afflictions due to his brother’s illness) manifests itself visually by black lines that overtake his brother’s (and his own) body. The harsh shadows and intense line work that David B. uses throughout not only provide great visual appeal, but they serve to make scenes claustrophobic, heightening his own tumultuous relationship with himself. Cities press in on him as he struggles with his relation between his work, his brother, and himself, and he becomes a raging dark figure pressing against walls that are bending and breaking perspective (pg. 295).

I was very interested in the fragmentation of self that David B. presents throughout the narrative: the so called “mythical creatures” that he adapts from novels and talks to when he seeks solace in the woods surrounding his family home. In a technical sense, they allow the narrative to progress without intense internal monologue, but they really act as a coping mechanism for David to vent his confusion and frustration with the hardships he is facing due to his brother’s illness: pieces of himself that he can visualize physically in order to make sense of it all. The progression that he makes is quite lovely: from their creation, to almost dependence (David remarks on pg. 230 “It’s just that these days I need you a lot.”), to finally, abandoning of these figures, because he is able to handle his problems all on his own, for better or for worse.

In some regards, it is a little difficult to connect to the circumstances David B. presents, but his ability to engulf the reader in just enough supplementary information is crucial to retaining the immersion between narrative and reader. Through his art, writing, and detail, he is able to present a very personal story, but still have it relate to and impact a reader: I found myself needing days to process everything, because I was left with an almost haunted feeling. There is something very visceral about the struggle that David B. portrays with himself, and I found myself connecting with it on a very core level. Epileptic is definitely going to get various re-reads from me, because it’s just one of those graphic novels you can’t take in all at once, because it’s just so dense; you finish it, and you feel like you’ve missed so much.

Emily Kardamis

Comics As Poetry: Emily Kardamis

Emily Kardamis: Through the Woods by Emily Carroll

Through the Woods

I’m usually not a huge fan of the horror genre, in any medium: traditional horror movies rely on exploitive jump scares and other gimmicks to set the viewer on edge, and if they do have a more mysterious element to them, they tend to ruin it by revealing the “monster” too early. The fear and intrigue is often in the unknown, in what is left unanswered at the end of the story, in what haunts you as you continue about your own life as normal, but now—subconsciously—checking every dark corner a little more thoroughly than you normally would have. This, however, is where Emily Carroll’s Through the Woods excels: it doesn’t spell out the mystery for the reader, and it leaves that haunting feeling after each story that sticks with you like a haze throughout the rest of the day.

Artistically, Through the Woods is phenomenal. Emily Carroll’s switch between fully colored panels and selective color is extremely powerful, especially in stories like His Face All Red: the soft and subtle tones throughout the story are contrasted extremely by any depiction of blood or similar applications—a flat, jarring red against the soft rendering of the figures and setting around it, making it not only visually separate from the surroundings, but suggests an otherworldly quality to those things containing it, that they do not belong in the world for one reason or another. This color contrast is carried throughout each story, giving an cohesive aesthetic to the entire work (the brother in His Face All Red, the setting sun in Our Neighbor’s House, the ghost in My Friend Janna, and so on).

Story-wise, each tale within Through the Woods not only stands on its own, but works to emphasize a through-line of unease and an unsettled feeling in the reader: each of Emily Carroll’s stories is horror in the most beautiful way, ethereal and haunting. It is a misconception that a story needs to answer all of the questions it proposes; in fact, a fantastic story leaves the reader with something to ponder, a mystery left to solve, and each story in Through the Woods is open-ended enough to leave you wondering about the shadows that are presented throughout each story.

There exists no clear lines in Through the Woods: there are no heroes or villains, only the explained and the unexplained, and much of both blend into each other: what is fate of the main character in My Friend Janna, now haunted by the same entity that was Janna’s demise? And this is the genius in Emily Carroll’s writing: the reader is left with work to do after each story’s conclusion; the specter of the mystery haunting them much like the unexplained monstrosities that haunt the main characters in her work.

Additionally, and it may seem like a small detail, but Emily Carroll’s hand lettering and organic panels really ties the entire graphic novel together. Her letting feels like the voices of each character, the narration, the spooky and unexplained voices that echo through homes, changing in weight and clarity as necessary.

As a whole, Through the Woods is much more than a graphic novel; it is an experience that will stay with you long after you have finished it, leaving you wanting—but also fearing—more.

Comics as Poetry: Emily Kardamis

Emily Kardamis

Words: Emily Kardamis

Emily Kardamis

Emily Kardamis

In Detail: Emily Kardamis

Comics as Response: Emily Kardamis

Comics as Review: Emily Kardamis

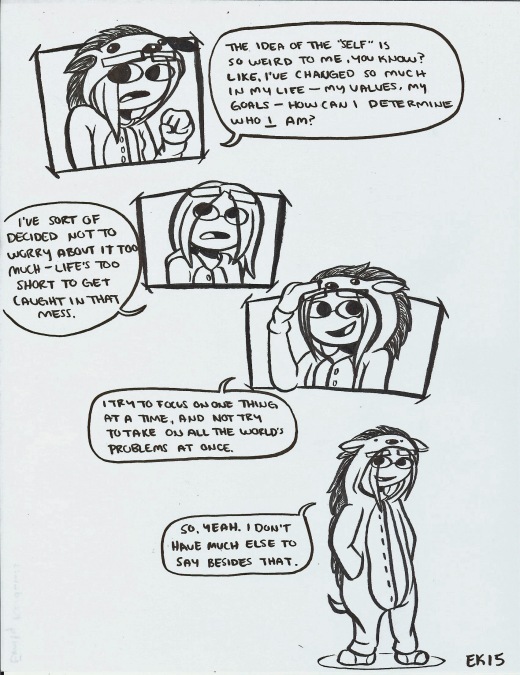

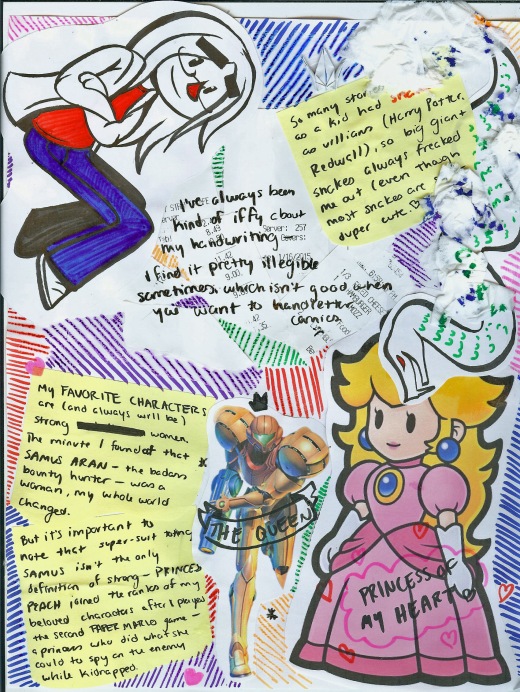

Emily Kardamis: Scrapbooking the Self

Emily Kardamis

Emily Kardamis

Emily Kardamis

Alright: imagine the sun. Mostly focus on the size of the sun—you could fit about a million Earths inside it. That’s pretty darn big, and the sun is technically only a middle-sized star, which means there are stars out there that are even bigger. How do you wrap your head around that? It’s hard enough trying to imagine something as big as a million of the planet we live on (gold star if you can actually do that, by the way, because I sure can’t. I can barely fathom the fact the fact that all of the United States and several other large countries can fit into Africa. Spatial awareness is weird and baffling), but then thinking of something that could be as big as a billion of that? Pretty weird.

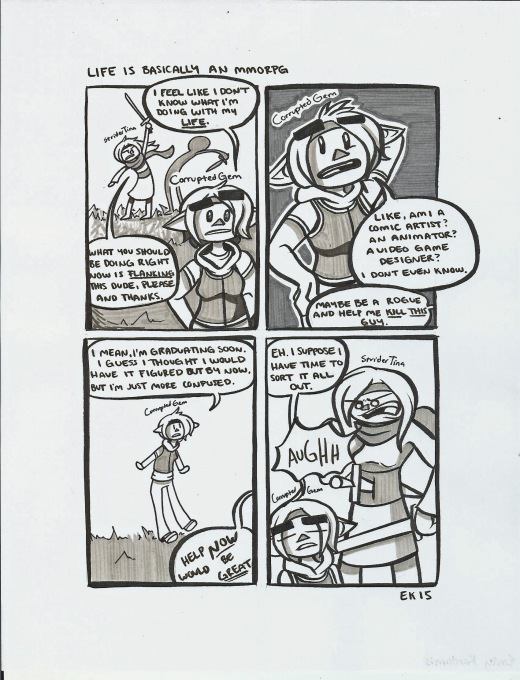

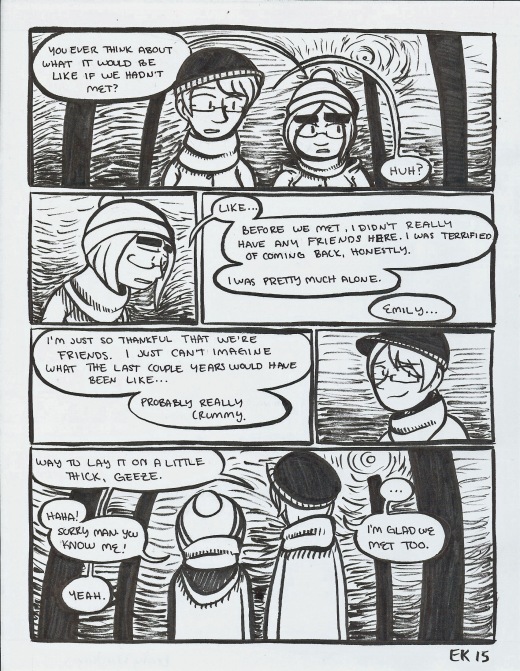

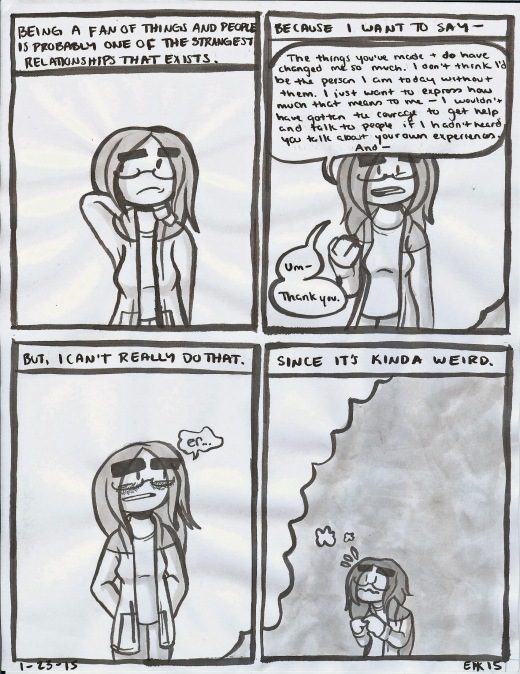

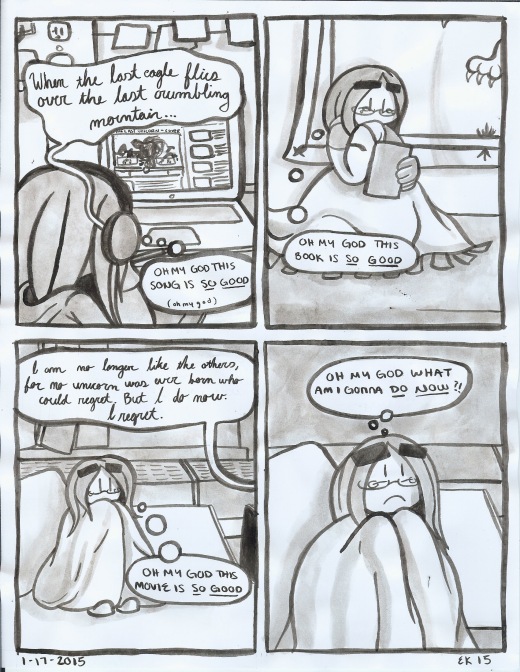

What I’m trying to say here is that my love of comics—if quantifiable—would probably be as big as twenty of those huge stars. Both reading and creating comics have been a constant in most of my life: they’ve become a comfort, something familiar and inviting, and also a place where I can express who I really am as a person. I’ve always been someone who viewed and remembered life in narrative: in little packets of episodic stories, often branching off on tangents organically and sporadically (like the whole star thing). With comics, I can really express that innate part of me in the most pure way: sure, I enjoy writing, but it’s the words combined with the visuals that really creates something larger than the sum of its parts.

And there’s just so much you can do with comics! You want to tell a story about an intergalactic space princess who’s off living a life of crime as a pirate? Go for it! Want to talk about a personal issue, like anxiety or depression? By all means! Just want to show some silly moments in your life, or tell some jokes? Make a comic! You can do anything with the medium, and anyone can use it to tell their stories, practiced artist or not.

Comics have become increasingly accessible as well: my main introduction to graphic novels (not just comic strips that I grew up on) were comics posted on the internet, both long, sweeping narratives and short little bursts of stories. I think that really had a huge influence on how I view my work: I want to share it, connect with others through it, and being able to put comics online and share comics with others through a simple link is so important to me, because it opens the door to people who don’t have those years of experience creating to get published, and gives artists, writers, and readers who might never have access to the medium a huge platform to work with.

For me, there’s just something pure about comics: I can speak totally from the heart, unfiltered, unedited. The self that exists in my comics doesn’t have to deal with the pretention of appearances or reputation: it’s just me.