Tag Archives: 2015 Sara Kear

Sara Kear

Sara Kear

Sara Kear

Sara Kear

Sara Kear: Through the Woods by Emily Carroll

Essay 3: Emily Carroll’s Through the Woods

I picked up Emily Carroll’s Through the Woods mostly based on the cover. I’m a sucker for richly designed visual allusions to little red riding hood. In this case it is blue riding hood, but the result is still the same. In the span of two evenings I read the whole book of five stories, an introduction and a conclusion. And as soon as I finished it I was flipping back through to see the sixth and seventh stories, found between the introduction and the conclusion as well as the story found between the cover pages and the end pages. I was impressed by the cohesiveness of all these stories bound into one awesome, chilling work of art.

It was not just the red riding hood allusion that caught my interest. It was the colors. The whole book is a study in how color works to affect a mood. The stark shifts from black to white to red with each turn of a page create a sense of palpable shock and tension that is delicious in the same sense as reading scary stories before bedtime. Every time a saw a page splashed with red I could feel a tiny jump in my chest, the unsettling indication that something is not right.

This feeling fits perfectly with how Carroll ends her stories. If ‘ends’ is the right word. Not one story has a completely finished ending. Instead the end is cut off right as the sense of doom is at its highest, leaving me, once again, with that unsettled gut flip feeling that something awful is about to happen. She did this over and over with each story. But when the last story came around and the brother was driving his sister back to the city I was sure it would end resolved and happy and safe. I thought, Carroll will end this one differently because it was the last one and one of these stories would have to end better than the rest. And then the brother turned out to be a monster! I loved the way she handled tension with her resolutions in all the stories.

Her language was also gorgeous, fit to go along with the images. In “A Lady’s Hands Are Cold” I could hear the dead woman singing. And I love how she placed her words as well, letting the bend and curve and blend with the drawings, truly becoming a part of them. Again, one of my favorite examples of this is in “A Lady’s Hands Are Cold” where she put the singing in swathes of red curling through the blue pages.

One of my favorite parts about the book is the wordless story set between the beginning pages and the ending pages of the girl in the blue cloak. When I looked at the ending illustrations of the girl going through the woods, the dire tension of the previous stories’ resolutions colored my perspective of whether she would make it home on the last page. The whole scene was splashed Carroll’s bright red of doom. It gave me the feeling that something terrible was going to happen to the girl even as she was almost safe home. The extra story and the introduction and conclusion made this book a complete workof art in a way I hadn’t imagined before. It is a work of art that, as you view it, also gives you spine chilling stories along the way, creating an unforgettable experience.

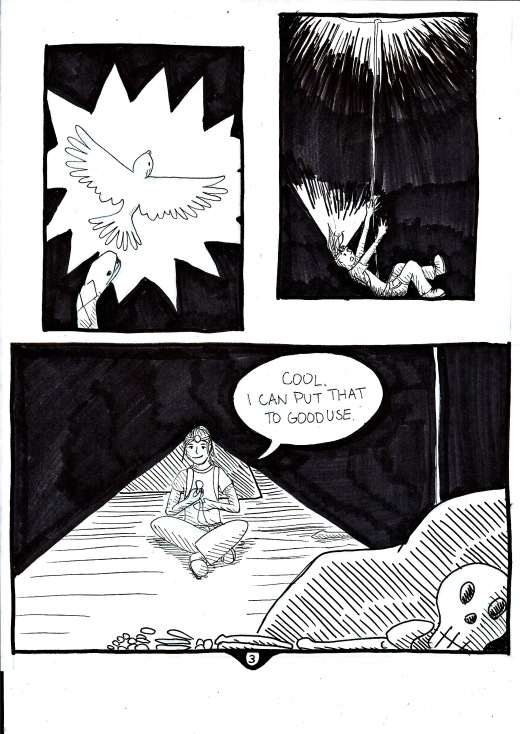

Sara Kear: Epileptic by David B.

David B.’s graphic novel, Epileptic, is a ranging epic that melds his experiences in reality with his forays into his own fantasy world. And even David’s reality was more mystical than the average childhood with his parents seeking many different spiritual cures for his brother’s epilepsy. But as much as the story followed Jean-Christophe’s descent into epilepsy – or his assent up the mountain of his disease as B. depicted it – it also follows the young David’s own struggle. His struggle is both with breaking free of his brother’s disease and with his crumbling sense of the difference between how the world is and how he perceives it.

All of the richly conceived images in this book are about perception more than they are about the inarguable truths of the mundane world. He sees his dead grandfather as a bird in a suit, has nightly visits with the devil, a skeleton and a cat-man and leaves his imaginary armor in the safe-keeping of Genghis Khan. And yet, by no means does that make this a fantasy story. He tells these strange companions that he hasn’t “been fooled into believing” they exist (221). But at the same time, he admits to needing them. These imaginary companions and creatures he injects into his life are his way of making sense of the world and of surviving it. I like how this mirrors my own sense of my creative life. Making stories and other art has always been my survival technique, both as an escape and as a way of indirectly dealing with all the difficulties living can bring. So in this, I was able to identify with David and his particular way of experiencing the world.

It is also this blending of actual with imaginary that brings out a greater truth. If Epileptic was filled with images portraying events exactly as the looked, the way any observer would see them, children in streets in the correct proportions when compared to houses, a man as just a man as opposed to a man with a cat’s head, they would lose all sense of this personal truth. By joining the actual portrayals with imagined components, or personifying his brother’s disease as a coiling monster, B. is able to delve into a deeper meaning. He is able to overlay everything that happened with how the situations felt. This communicates better than any other medium – in a graphic novel this communication is instantaneous and primal – a full scope of experience, perhaps coming closer than anything to what really happened and what David really went through.

The end caught me in the heart. In the end David is on a horse with his brother, talking about how much they shared in common, with reading and drawing comics, and how the were pushed apart by the disease. But the last lines speak of how they are both inextricably linked, sharing the same face and facing the same demons. An ending as beautiful as it is sad. But even here, the fantastical images play their part. The final image of David sitting on the horse, looking directly at the viewer, and his brother sleeping on the horse’s belly, gives, if not a sense of hope that they can be brothers like when they were children, at least a sense of closure. Perhaps David B. meant that if his brother could share his face, he could share his story too, somehow fulfilling Jean-Christophe’s wish that he could have written the story of Epileptic himself.

In Detail: Sara Kear

Words: Sara Kear

Sara Kear

Sara Kear

Sara Kear

Sara Kear

In Detail: Sara Kear

Sara Kear

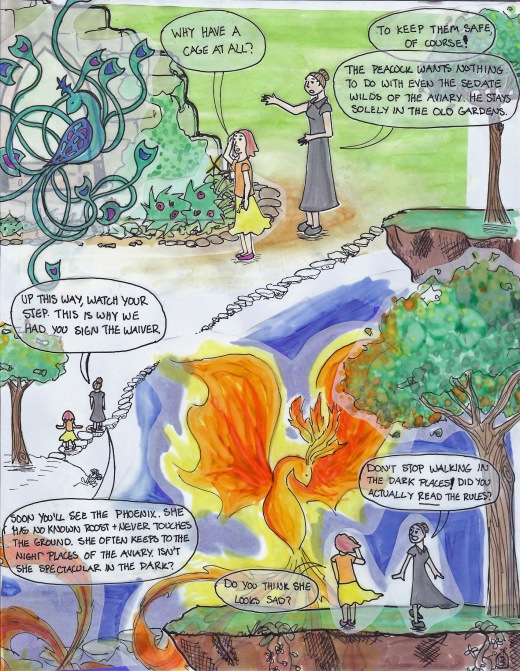

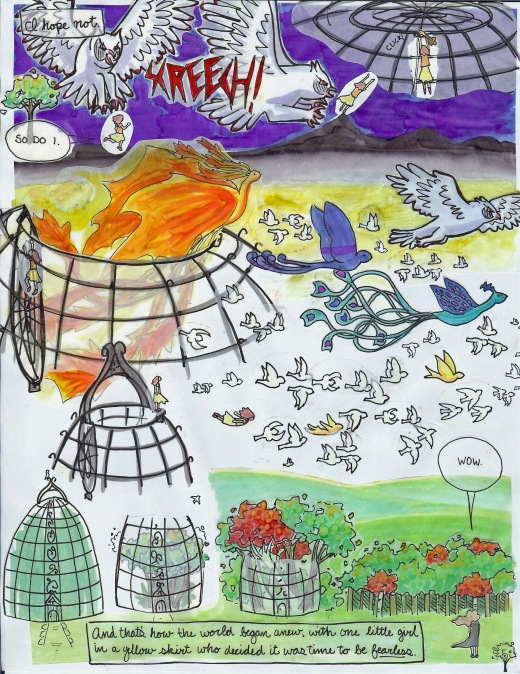

Comics as Response: Sara Kear

Comics as Review: Sara Kear

Sara Kear

Sara Kear

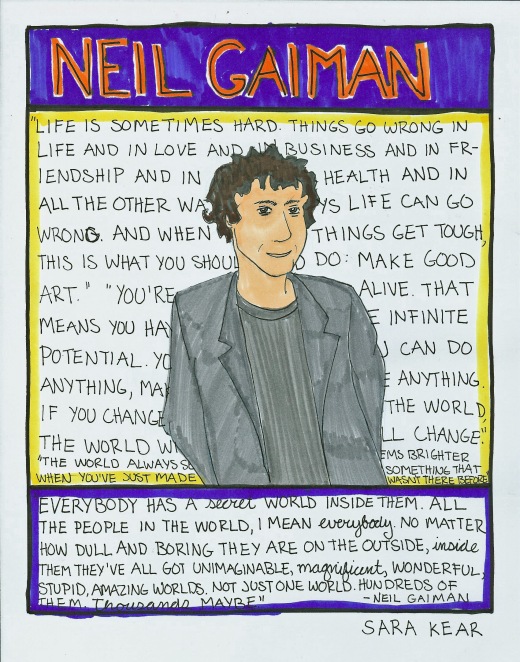

It is my brother’s fault. When I tell him it’s his fault he smirks because he knows it is true. He nods, congratulating himself for a job well done, and says, “You’re welcome.” He can’t take all the blame, I guess. It is also Bill Watterson’s fault. Before my brother showed me the full color, glossy pages of a Spiderman graphic novel, Bill Watterson had me at the Sunday Comics. Calvin and Hobbes showed me a world where humor and imagination met a world of sympathy and philosophy. For a good portion for my childhood I went to the Sunday comics like a devout follower goes to church.

My mother and father are to blame for what came next. They are both art lovers and artists themselves and opened an office and art supply store when I was three. Give a five year old Prismacolor pencils and Pigma pens and it is only a matter of time before she is lost to the world of making things. So I tried to emulate the Sunday comics and my brother’s vast collection of Calvin and Hobbes books with their word and picture stories as best I could. I took small pads of white paper, turned them horizontal and drew my first comic books. A few panels in a line on every page covered the daily escapades of all my pets, with the kind of humor and love a ten year old does best. (We had a chinchilla and a ferret as well as the usual cats, a dog, various gerbils and a four-and-a-half foot long iguana as ample inspiration.) I was ten and vastly proud of myself. And then I drew more comics. And I started writing stories without pictures, emulating all the books I read and could never get enough of. A passion for reading was the fault of both my mother and my sister. But even then, drawing the characters of my stories was one of my favorite ways to get my ideas on paper.