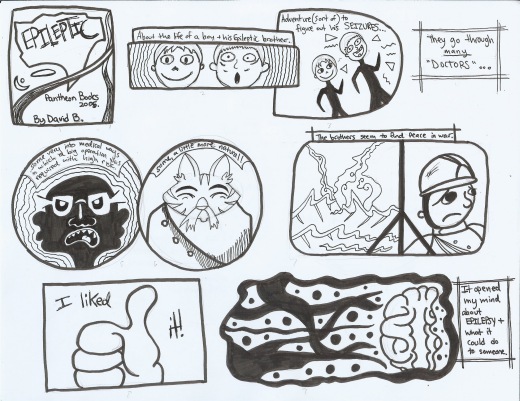

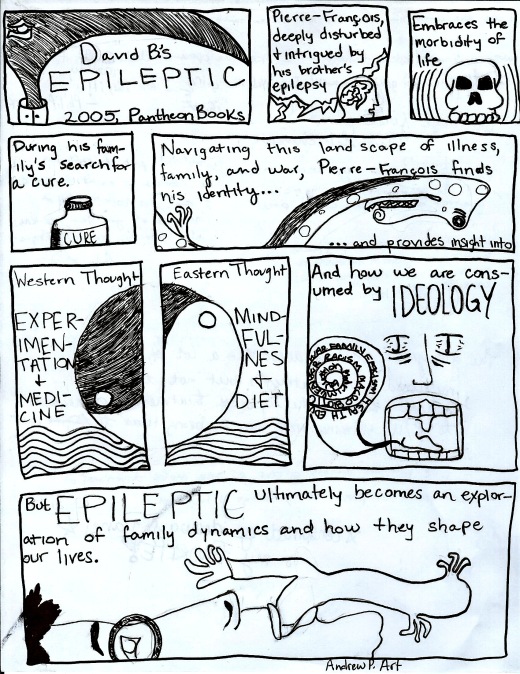

David B.’s Epileptic is one of the most impressive and visually stunning graphic novels that I’ve read so far. It is steeped in a commentary on war, ideology, and spirituality as much as it is grounded in dynamic family relationships. What impresses me the most is how highly stylized David B.’s work is, yet I’m drawn into the stark reality of Jean-Christophe’s epilepsy. The text of Pierre-Francois’s narrative often draws attention to how we are affected by ideology. I particularly appreciated the focus on Eastern vs. Western ways of approaching disease and health. Throughout the various communes that Pierre-Francois’s family visits, each places an importance on altering diets and practicing mindfulness. The Western doctors that the family visits, however, all focus on experimentation, pushing the limits of science and medicine. It’s not too often that a work manages to bridge the divide between ideologies. Such attempts may come off in the text as clichéd window-shopping for meaning. Even though this is exactly what Pierre-Francois’s family is doing, David B. manages to capture the psychology of this constant deferment of solutions in a sobering manner.

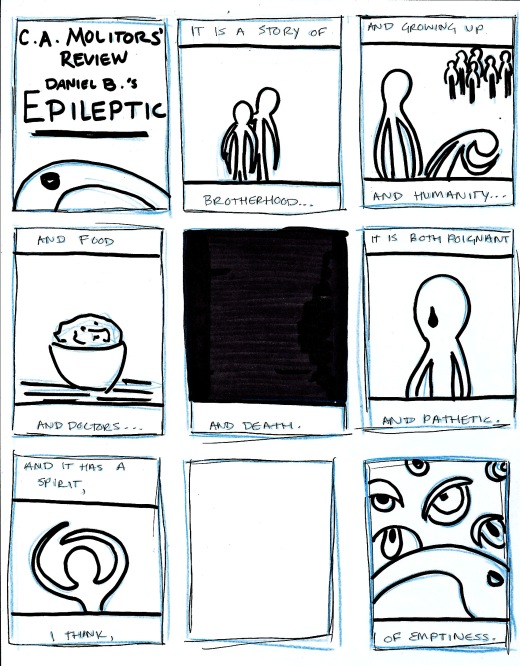

Although this is roughly an autobiographical work, I still think that this story’s most shocking element is that its perspective is not from Jean-Christophe. The oddity lies in the fact that we are learning about a disease from a second-hand source. This oddity is also what makes the work all the more gripping. Some may consider this work an appropriation of Jean-Christophe’s disease, a convenient plot device that might thicken the soup. This is not to suggest that a graphic novel written by his brother (who would have first-hand experience) would be any worse or better. Instead, David B. is telling a story from his perspective, which allows us to learn about Jean-Christophe’s disease alongside Pierre-Francois. The psychology of an individual experiencing a disease is quite different from a family member who bears witness to a loved one going through that same disease. The panels depicting Pierre-Francois and his mother having dreams about curing Jean-Christophe is one of the most touching things that I’ve ever read. As readers, we are not called to sympathize with and praise Jean-Christophe’s family members over Jean-Christophe for enduring such hardships that are a result of his condition. However, we are called to empathize with the situation. We all have valid stories worth telling. In this graphic novel, we are given the privilege and opportunity to learn with a family – David B.’s self-criticism shines through with his adult perspective.

The visual motifs that David B. inserts within his artwork contributes to the seemingly impossible clean-yet-grotesque aesthetic established in this graphic novel. The depiction of the dead grandfather as a man with an ibis head is so beautiful and subtle yet manages to transfer so much anxiety into this work. The ibis, as an agent of death in Egyptian mythology, serves as a constant reminder of our mortality. This ibis head is what looms over the two brothers on the cover of the graphic novel. It is also what appears to Pierre-Francois throughout his adolescence. What haunts us is often the unknown. Our own sense of mortality is the ultimate known yet-unknown. This is the paradox the Epileptic is wrapped up in. One of my favorite panels sums up the importance of this world. One page 304, the panel is dark, Pierre-Francois is headed back to his parents’ house and must climb a wall to reach his destination, he says, “I’m passing over into the Other World.” This graphic novel is a passing over into the Other World. We are entering into the lives of a family who is completely in the liminal gray space of the world. In between Eastern and Western, disease and cure, war and peace, wholeness and fracture. Epileptic is able to objectively illustrate these binaries by thriving in their muddled boundaries.